This happened a few years ago, when I was working as an SDET in a product company. At the time, it felt like just another sprint. Looking back now, it became one of those moments that reshaped how I test.

It taught me that users don’t read acceptance criteria, and that testing isn’t only about validating what’s written — it’s about predicting how real people will behave once the feature is live. They click around, skip steps, and try things we never imagine during sprint planning.

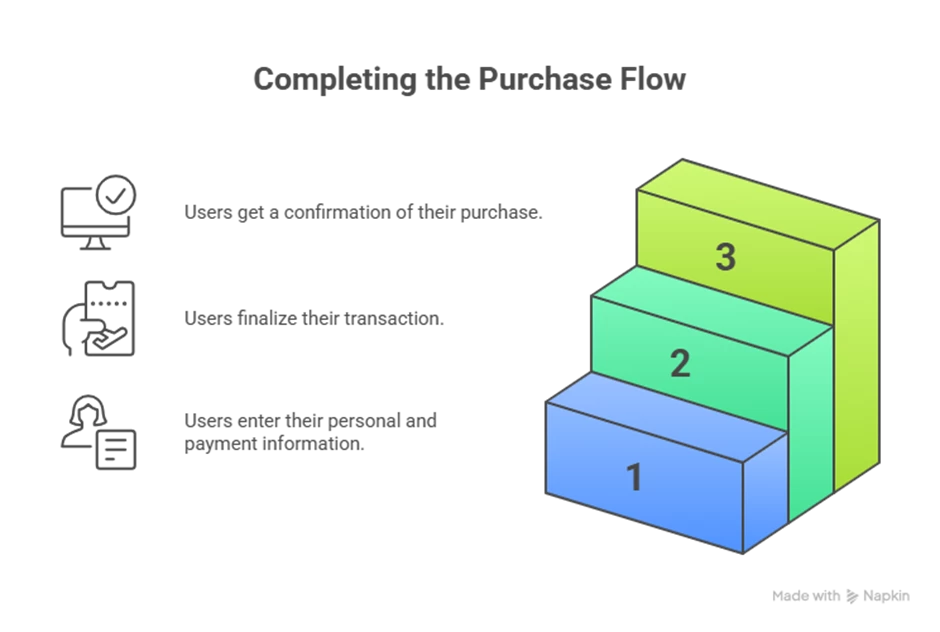

We were an agile team working on a transport and tourism e‑commerce platform based in London. This particular sprint focused on improving the customer journey, and one of the key deliverables was a new user‑details form that appeared during the purchase flow.

Some fields — like Full Name, Email Address, and Payment Details — were mandatory for checkout, while others — such as Alternate Phone Number, Special Requests, or Promo Code — were optional.

Our goal was to ensure the entire end‑to‑end experience worked smoothly, from filling in these details to completing payment and receiving confirmation.

Once the new user‑details form was built and integrated, I went through all the manual test cases we had for it. Everything behaved exactly the way we expected.

Our automation regression suite ran overnight and didn’t flag any failures. There were no high‑ or critical‑severity bugs open, and nothing in the backlog looked risky. The Product Owner reviewed the story and gave us the green signal. So, as planned, this user story went out with the rest of the sprint’s deliverables.

The team was confident. I was confident. It felt like a release that wouldn’t cause any surprises once it went live.

The bug that didn’t look like a bug

Two days later, our manager dropped a message in the team channel saying a customer had reported an issue. It wasn’t about a broken feature or a crash — just something that “didn’t feel right.”

The issue was this: the user‑details form was being submitted even when mandatory fields were empty, but only if the customer navigated back and forth using the browser’s Back and Forward buttons.

When I dug deeper, I realized this wasn’t a missed validation or a simple UI glitch. The browser was restoring old, cached form data when the user navigated back, and our system was still treating that stale data as valid input.

So, from the customer’s perspective, the form looked empty — but the system thought it already had the previous values. That combination of unexpected user behaviour and cached data created a scenario none of our tests had covered.

How did we miss this?

Once we managed to reproduce the issue, the real question wasn’t what went wrong — it was why. And the answer was obvious.

We had tested exactly what the acceptance criteria told us to test. We walked through the happy paths, step by step, and every expected flow behaved exactly the way it should. But we also assumed users would move through the journey in the same clean, linear order we had in mind.

This customer didn’t.

They went back. They jumped forward. They changed a few fields, and they skipped some mandatory ones entirely. That unusual mix of actions — never mentioned in the requirements and never discussed during planning — exposed the flaw.

Manual testing missed it because we didn’t test beyond the scenarios we expected.

Automation missed it because our scripts only checked the ideal flow with the ideal inputs. They never explored what happened when the user behaved differently.

And sprint pressure didn’t help. As the deadline got closer, the time we normally kept aside for exploratory testing just wasn’t there anymore. We were focused on finishing the planned test cases and closing the story, not exploring the “what‑ifs” that weren’t part of the acceptance criteria.

Fixing it. And fixing ourselves

Once we understood the root cause, the fix itself was straightforward. I walked the developer through the exact steps, and a small code change ensured the form data refreshed correctly when users navigated back and forth.

Before the fix went live, I retraced the customer’s journey — and then pushed it further. I tried the same flow on desktop and mobile, using different paths and variations to make sure nothing else slipped through.

On the automation side, I added a new test to cover this scenario. Not because automation had failed, but because it needed to evolve based on what we learned.

When the fix reached production, the issue was gone and the customer was unblocked.

The bug was fixed — but the lesson stayed.

What that bug taught me

This bug taught me a few things that still shape how I test today:

- Users don’t read acceptance criteria.

- Exploratory testing isn’t optional, even when automation is all green.

- Automation needs to evolve with real user behaviour, not just the specifications.

- Assumptions eventually show up as production bugs.

Most importantly, every escaped bug is a chance to improve how we test, not just fix a line of code.

Since that incident, I’ve approached releases differently.

I don’t stop at “Does this work?” I also ask, “How could this break if someone uses it differently?”

That small shift — from checking expected behaviour to being curious about unexpected behaviour — reduced production issues far more than adding more test cases ever did. Some bugs hurt. Some bugs teach. This one did both.

Thank you for reading! Hope, my experience could help you in preventing slippage of bugs in production.

About author:

I am a quality engineering professional with deep expertise built through years of hands-on experience in manual testing, test automation, and overall Software delivery. Passionate about simplifying complex testing concepts. Excited to collaborate with ShiftSync and contribute to the global testing community. Enjoy reading my articles here!